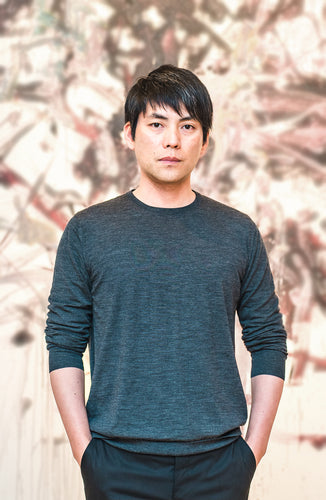

Splendid Architecture | SHOHEI SHIGEMATSU 重松象平

Creating Functional Artistic Spaces

SHOHEI SHIGWMATSU( 重松象平) is a partner of the OMA architecture office and is also currently the Director of OMA New York.

Born in Fukuoka in 1973, Shigematsu studied at Kyushu University’s Department of Architecture. After graduating, he moved to the Netherlands to join OMA in 1998. Later, in 2006, he relocated to the U.S. to lead OMA’s New York office.

Shigematsu has been a driving force behind OMA’s diverse portfolio in the Americas and Japan. Major works include Milstein Hall at Cornell University’s College of Architecture, Art, and Planning (AAP); a new museum for Quebec National Museum (Pierre Lassonde Pavilion); the Faena Forum, a multi-purpose venue in Miami Beach; the reimagination of Sotheby’s auction house headquarters in New York; and an event pavilion for the Wilshire Boulevard Temple in Los Angeles (The Audrey Irmas Pavilion).

Pierre Lassonde Pavillion at MNBAQ

After almost 20 years of working outside his native country of Japan, Shigematsu recently completed Tenjin Business Center in his hometown of Fukuoka and currently leads a number of large-scale projects across Japan, including OMA’s first tower in Tokyo.

Tenijin Business Center

Shigematsu has been a visiting professor at Cornell University College of Architecture, Art, and Planning (AAP), Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), and Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP). He is currently a professor of Human Environment Studies at Kyushu University and has been the Director of BeCAT (Built Environment Center with Art & Technology) since 2021.

IROHA: What projects are you currently working on, and what do you want to mention most recently or in the future?

SHOHEI: There are two exciting museum projects in New York—the New Museum in the Bowery neighborhood of lower Manhattan and the Albright-Knox Museum in Buffalo, a major city in upstate New York. For both projects, we are expanding the existing museum with new building additions to accommodate the cultural institutions’ ever-growing collections and diversifying public programs.

Albright-knox Museum

On the opposite coast, we recently completed a different kind of cultural space for the Wilshire Boulevard Temple, the oldest Jewish synagogue in Los Angeles, California. The Audrey Irmas Pavilion is a multi-purpose event space for both the congregation and the city that recontextualizes the historic Temple respectfully for today’s civic needs.

The Audrey Irmas Pavilion

Tenjin Business Center in Fukuoka was also completed around the same time. It was a great experience to be able to return to my hometown for both OMA's first ground-up office building in Japan and to oversee construction of a 265m skyscraper in Tokyo and a new subway station connecting to it. The tower has a highly public interface and integrates public amenities such as a grand station concourse, green landscapes, and cultural venues with offices, hotels, and retail stores.

Toranomon Hills Station Tower -Tokyo

IROHA: How do you see your role in the society or in the business.

SHOHEI: I believe my role in the grand scheme of society is to bridge the cultural gap through architecture. Architecture is arguably a human necessity. And while individual experiences of a space can be diverse, the shared occupation of it offers the potential to embrace and advocate for equity. Architecture can foster a mixture of people and hopefully reconcile differences.

On the other hand, the glass ceiling is still very present. In the U.S., over 70% of architects are White and about 13% Asian. Despite the increasing enrollment of Asian students across architecture schools, the number of Asian architects in leadership positions remains few. Against these figures, I feel privileged to be in my position and have a responsibility to represent and inspire not only Asians but all minorities pursuing paths in the industry.

Pierre Lassonde Pavilion at MNBAQ

IROHA: Based on your background, do you have any advice or message for young people who want to follow in your footsteps?

SHOHEI: Moving across many countries from an early age and having worked in countries across Europe, Asia, and the Americas, I had a lot of exposure to diverse cultures and have grown accustomed to observing differences quite openly to learn from them. I think this mindset is apparent in our studio culture—investigating a client’s or site’s conditions and constraints, as well as broader economic or political shifts and issues, with an open mind and proactive curiosity to absorb and reflect contemporary values in architecture.

I would like to encourage younger generations to always observe what’s happening in the world and indulge in personal interests outside of design. It’s about developing a keen eye for identifying changes in society that can eventually be expressed through architecture.

IROHA: Outside of work, what are you most interested in right now?

SHOHEI: Food—eating, and more recently cooking (since the pandemic). It’s a human necessity, but also a way to connect with different cultures. I think my interest in and appreciation for food beyond the dining table comes in part from my Japanese identity. But as architecture started to become globalized and homogenized, I became intrigued by how food could be simultaneously super-global and super-local. My interest led to the creation of a studio called Alimentary Design at Harvard, where we researched food as a means to look at architecture and urbanism.